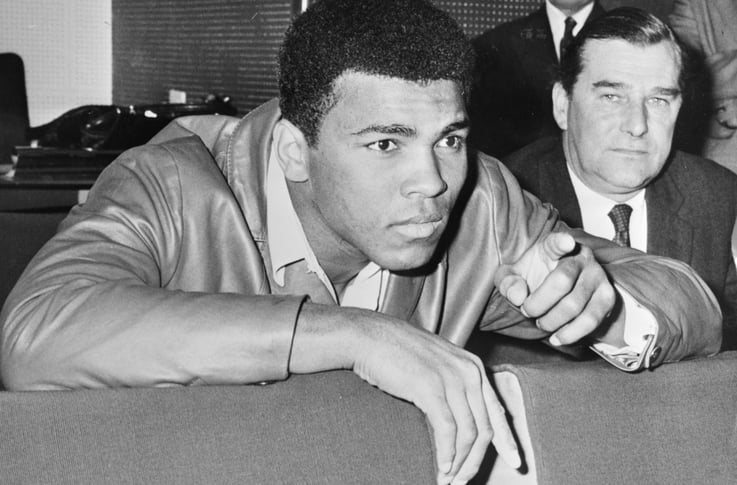

It intrigues me that someone like Muhammed Ali, who was highly respected for his contributions to the boxing world and his philanthropism, could succumb to septic shock! As we educate our caregivers on the importance of early detection and prompt medical treatment, this is a good reminder that even with the highest level of care, an elderly, compromised body is at risk. None of our residents is protected from sepsis—there is no immunization, only early detection and prompt treatment.

What Is Sepsis?

Sepsis is a complication caused by the body’s overwhelming and often life-threatening response to an infection. It can lead to organ failure, tissue damage, and death. An infection that is getting worse and not treated can lead to sepsis, so urgent treatment matters. Sepsis is a medical emergency!

Sepsis most often occurs in people who:

- Are over the age of 65 or less than one year old

- Have chronic diseases (such as diabetes) or weakened immune systems

Sepsis is most often associated with infections of the lung, urinary tract, skin, or GI tract. Common germs that have been identified as causative factors for sepsis are Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, and some types of Streptococcus.

Sepsis:

- Encompasses a spectrum of illnesses that ranges from minor signs and symptoms to organ dysfunction and shock

- Ranks in the top 10 causes of death in the elderly and infants

- Is influenced by the virulence of the pathogen, the portal of entry (location in the body), and the susceptibility and response of the body

- Is a clinical diagnosis—laboratory tests are commonly negative

Remember, even healthy people can develop sepsis from an infection—especially if it isn't treated properly—so managing infections in your care team is also important!

Sepsis begins outside of the hospital for nearly 80% of patients. Seven in 10 patients with sepsis recently interacted with healthcare providers or had chronic diseases requiring frequent medical care. This presents a prime opportunity for both preventing infections and recognizing sepsis early to save lives.

Controlling and Preventing Sepsis

Recently, the state of Ohio Health Association established a board-directed goal to lead the nation in quality improvement on key issues as identified by OHA members. The objective was to reduce severe sepsis and septic shock incidence and mortality by 30 percent by 4th quarter, 2018. Their tactic was to lead a statewide sepsis reduction hospital collaboration to improve implementation of best practices—specifically early identification and treatment. The state of New York also embarked on a Sepsis awareness and reduction program.

So what can we do as healthcare providers? Prioritize infection control and prevention, sepsis early recognition, and antibiotic stewardship. Train your frontline staff to quickly recognize and treat sepsis.

- “Think sepsis” in any person with a suspected infection

- Sepsis may present with non-specific symptoms and signs, and WITHOUT fever

- Have a high index of suspicion of sepsis in those who are over 75 years old, are immunocompromised, have a device or line (IVs, PICC lines, etc.), or have had recent surgery

- Use risk factors and any indicators of clinical concern to evaluate a resident’s risk for sepsis

In some residents with early sepsis you may observe:

- Shivering, fever, or very cold (remember, geriatric residents rarely have an elevated body temperature until they are critically ill)

- Extreme pain or general discomfort (“worst ever” or use the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating System for residents unable to verbalize pain)

- Pale or discolored/mottled skin

- Difficulty waking up, confusion

- “Feel like I might die” (believe them—statistically it's a real risk)

- Shortness of breath, difficulty breathing

Remember, your direct care staff know your residents the best and should be alert to subtle changes in sensorium, mobility, interest, wakefulness, appetite, etc. Using the “stop and watch”, “SBAR”, or similar tool has proven to be helpful in early detection.

Unfortunately, with the penalties related to re-hospitalization, we may discourage transfers to the ER even when they may be warranted. Be sensitive to this as you educate your staff. The old motto, “when in doubt send them out” may not be prudent today—however, tread carefully if the decision to transfer or not is being made by laypeople versus clinicians.

Trust your clinical team, trust your gut. Remember, you can’t change a negative outcome!

Next Steps

- Follow us on LinkedIn

- Get more great content—subscribe to our blog

- See how QA Reader gets more out of your EHR system